Recently, I started volunteering at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View as a docent (tour guide), where I guide visitors through tours covering the past 100 years in computer history.

This has been one of my most intellectually fulfilling experiences, and here are the top lessons I learned:

1. Technological progress shouldn’t be taken for granted

Computing has permeated our lives so deeply that we often take things for granted. We don’t wake up every morning and exclaim to ourselves: How wonderful it is that I can use my finger to swipe on a tiny screen! How amazing it is that I can video chat with a person across the world using the Internet!

Walking the galleries of the Computer History Museum reminded me: There was a time when computers had no screen and no mouse. There was a time when there was no Internet, no email, no Google.

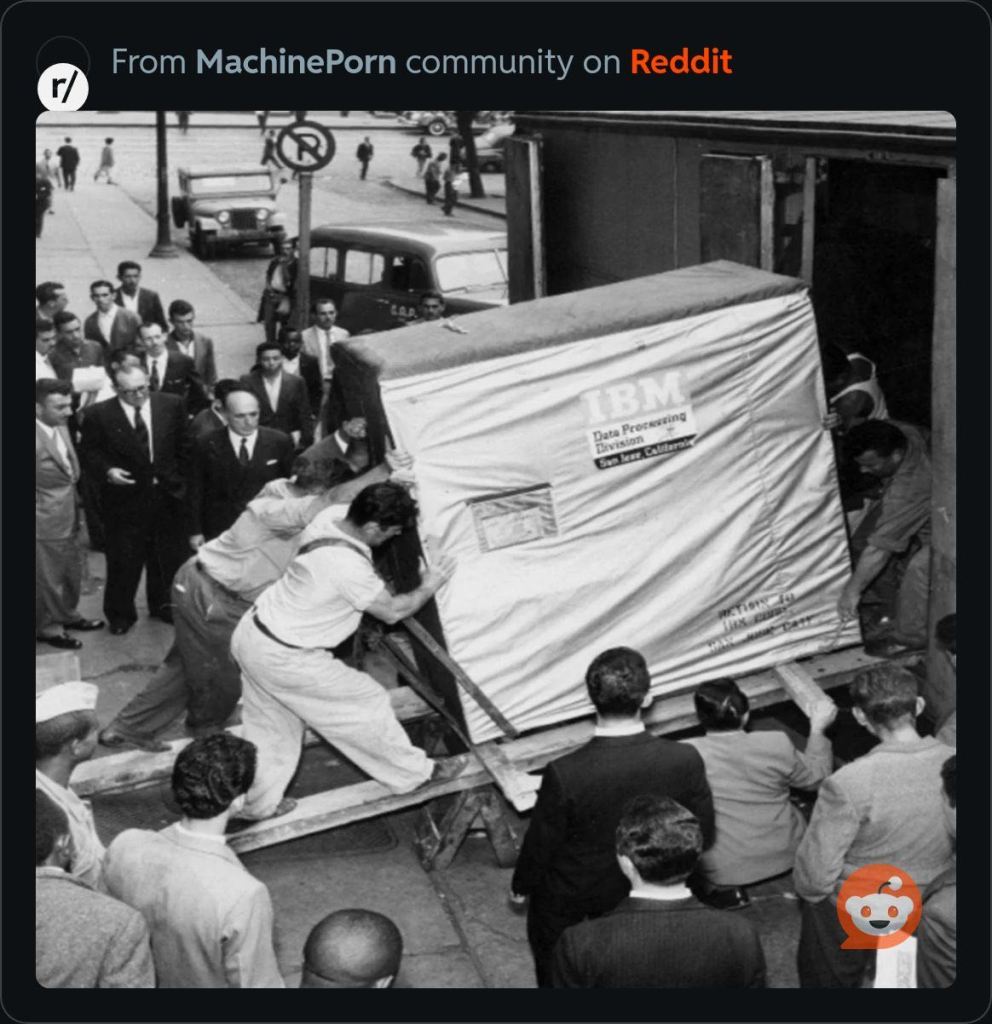

The world’s first commercial hard drive, the IBM RAMAC (shown below), had just 3.86 megabytes of storage, roughly equivalent to 1 photo on your smartphone today.

ENIAC was the size of a three-bedroom house, and now we each have millions of times more computer power – the smartphone – in our pockets. How long did it take to progress from ENIAC to ChatGPT? Less than 80 years.

If you really think about it, it does feel like magic.

Sometimes it feels like these technologies just magically popped out of nowhere. Once we get used to something, it’s so easy to take it for granted.

But we shouldn’t take technological progress for granted. Everything happened because someone invented something; someone pushed the technology forward; a lot of people put in a lot of hard work to make these things happen.

Moore’s Law is not a law of nature – it’s more like a self-fulfilling prophecy. It was not guaranteed to happen. It only happened because many, many smart people wanted it to happen and worked hard to make it happen.

Telling stories about these visionaries and pioneers rekindled my passion for technology. As professionals working in tech, we often get too steeped in the busyness of day-to-day work, and lose sight of the bigger picture. It helps to zoom out and remember why we’re doing what we’re doing: technology pushes the human race forward.

Keep the wonder in your eyes, and appreciate the magic in our lives.

2. The path from innovation to impact is not a straight line

The company that first comes up with a technology may not be the same one to turn it into a hit product.

A prime example is Xerox PARC. Xerox had the first what-you-see-is-what-you-get word processor, but it was Microsoft that gave us Word. Xerox had the first computer with a GUI and a mouse, but it was Apple’s Macintosh that brought them into the mainstream.

We often talk about “ChatGPT wrappers” in the AI age. You could argue that all past innovations have been “wrappers” to some extent; everything was built on top of the shoulder of giants that came before. The line between “evolution” and “revolution” is sometimes very blurry.

Contrary to popular imagination, innovation isn’t about some lone genius having a “Eureka!” moment in their garage. Innovation thrives on cross-pollination, on bringing together diverse people and ideas. It’s not a straight line; it curves and turns and criss-crosses. It’s messy.

3. Being a museum docent is a lot like being a product marketer

I think volunteering as a museum tour guide is very similar to my day job as a marketer for technology products.

The challenge is: How do you make a diverse group of people care about a bunch of old computers? How do you translate technical concepts into simple, layman language? How do you recount obscure tidbits of history so that they are made relevant to what’s happening in tech today?

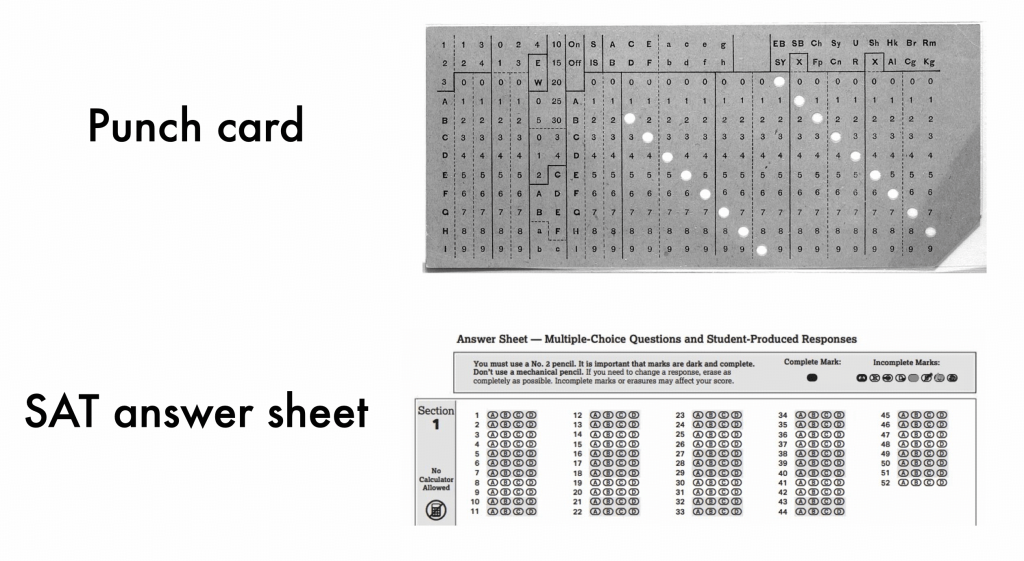

I find analogies extremely useful. One day I was explaining how punch cards work, and a member of the audience exclaimed: “Oh, it’s just like those SAT answer sheets.” I thought to myself, what a wonderful analogy! The holes you punch in cards are just like the circles you fill out with no. 2 pencils during standardized tests. Both convert data into a machine-readable format.

Most people haven’t encountered punch cards in their lives, but almost everyone has taken a standardized test. So I incorporated this analogy into my script. I love seeing the “oooh, I get it now” look in people’s eyes when I explain concepts like these.

Another example is Fairchild Semiconductor and the origin of Silicon Valley. I talk about how many people left Fairchild to start their own companies, and how this culture significantly contributed to the birth of Silicon Valley. But how is it relevant to today’s tech scene? I ask the audience to consider the people who have recently left OpenAI to start their own AI startups. Will OpenAI be the Fairchild of the AI age? I don’t know the answer, but questions like these really help the audience relate historical facts to the present moment.

4. The Innovator’s Dilemma is real and extremely relevant today

Whenever a new revolutionary technology comes along, we see the Innovator’s Dilemma happening in full swing.

I recommend everyone working in AI to read (or re-read) all of Clayton Christensen’s books and watch his talks on YouTube. I guarantee it will be worth your time. The theory sounds simple, but if you really dig into it, there are so many nuanced details that change the way we look at AI companies today.

The Innovator’s Dilemma is probably the most beautiful management theory of all time, and it has stood the test of time. If you are a startup, it can help you think about positioning and how to take advantage of the weaknesses of larger incumbents. If you’re a large company, it can help you think about how not to get disrupted.

5. For startups, timing is everything

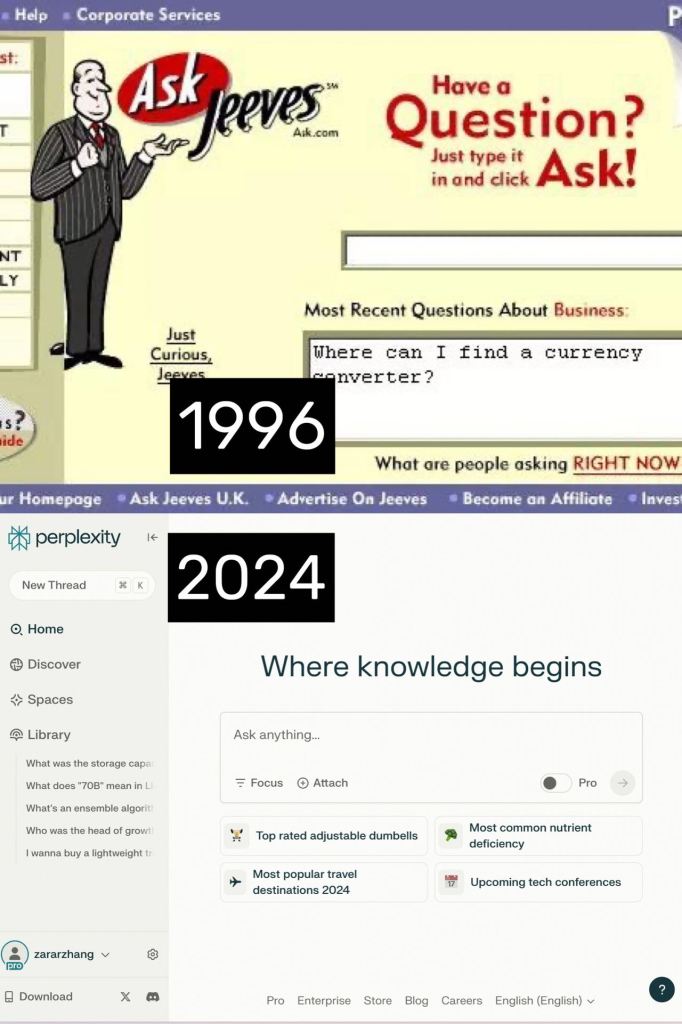

One of my favorite tidbits of Internet history is a website in the 90s called AskJeeves. You could ask Jeeves a question in natural language, and Jeeves would fetch the answer for you from the web.

Yeah, AskJeeves was basically the Perplexity for the 90s.

But unfortunately, in the 90s, there was no generative AI or large language models yet; the natural language processing technology was extremely rudimentary. So the answers were not very good. AskJeeves couldn’t compete with Google and faded into obscurity.

I love this story, because it is a classic example of “the right idea at the wrong time”. The vision was great, but the technology was not at the right level of maturity to make it happen.

For startups, timing is everything. If you come in too early, your product will be really bad because the technology is not ready. If you come in too late, the market will be already crowded with competitors.

Timing the market means having a deep understanding of the technology and its rate of progress, as well as the gumption to skate to where the puck is going.

6. “Being at the right place at the right time” is extremely underrated

This is a lesson on personal career planning.

When I studied the lives of the most successful entrepreneurs and technologists in history, I realized that their most underrated common trait is probably “luck”.

Of course they were all extremely talented and hardworking. But they also happened to be at the right place at the right time. What do Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Eric Schmidt, and Tim Berners-Lee have in common? They were all born in 1955, and came of age just as the personal computer revolution was taking off.

This is part of the reason that I moved back to the Valley last year. I felt like with the advent of the AI revolution, history is being made right now, and Silicon Valley is the place to be.

I highly recommend everyone working in tech to pay a visit to the Computer History Museum. Silicon Valley is often too preoccupied with imagining the future to think about the past. But we don’t have data about the future; we only have data about the past.

You’re welcome to join my tours, which are open to the public:

December 8 (Sunday), 2-3pm

December 14 (Saturday), 2-3pm

December 21 (Saturday), 12-1pm

No sign-up required; just show up!

For those who can’t visit, here’s a list of recommended resources I compiled if you want to learn about computer history.